Written by James Blumenfeld

Photos by James Ray

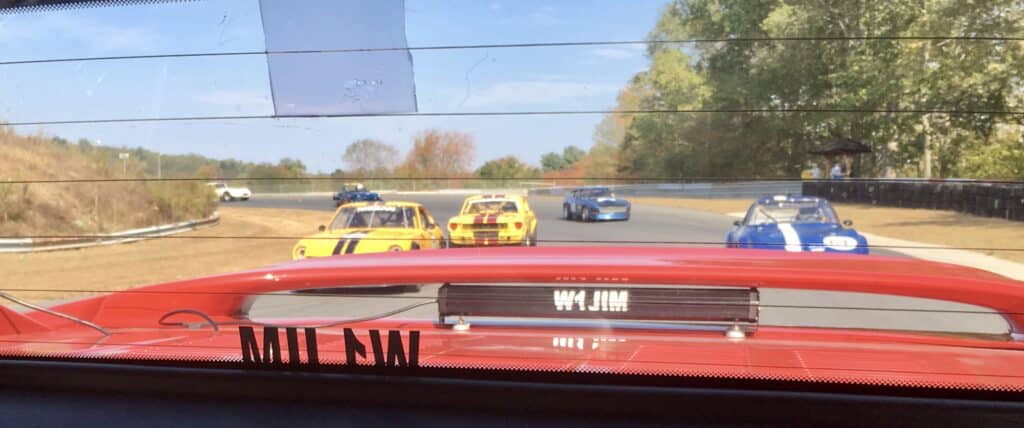

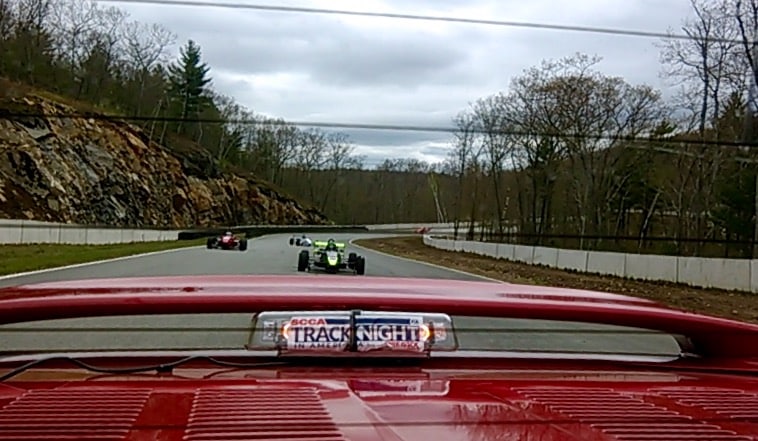

Inside the Pace Car

The radio crackles “Grid to Race Control – one minute.”

“One and go” responds Race Control.

On go the pace car strobe lights, snick it into gear – and hope that I don’t clumsily stall it. I tap the start button on my digital timer – a sophisticated instrument that looks suspiciously like one found in the kitchen goods aisle at your local Target. “One and go,” means in sixty seconds the quiet will be broken as the cars gingerly emerge from the grid and line up behind me for the pace lap.

“Cars on course” announces the Flagger’s Net radio.

I run 3 radios in the pace car, two for monitoring the Flagger and Control nets and the third used to communicate on a dedicated channel with Race Control.

I call in “pace car underway” and start crawling forward at a mere 5-10 mph.

As the cars line up in two rows behind me, I stick out my fluorescent gloved left hand to signal that we’ll be going slowly until everyone is in position.

“Pace car, you have the field” intones Karen on the grid.

I pull my hand in and gently accelerate – time to get the party started as the field initiates the ritualistic zigzagging to clean and warm their tires. The larger the field the gentler I need to accelerate so that the field doesn’t get strung out. Accelerate too abruptly and while the first few cars will be able to keep up those deeper in the pack will get left behind. If I go too slowly, well then everyone is frustrated, and time is wasted. It’s much like an oscillating multicolored slinky made up of dozens of cars.

I’ve driven thousands of laps in competition – but there I’m primarily looking ahead and to a lesser degree around me. In the pace car, while I’m looking ahead for any possible debris on track and to avoid the off-line marbles, I’m also looking far behind to make sure there isn’t a growing gap or unforeseen calamity that could forestall the start of the race.

As we approach turn nine (coincidentally it’s turn nine at NHMS, Thompson and Palmer), I turn off the strobes, radio “Pace Car lights out at nine”, stick my hand out for a moment, and slow down a bit to allow the pack to compress. Now it’s up to the competitors to get lined up and compress the pack.

I turn up the Flagger Net radio and listen for station ten (my heroes) to give a pack report – hopefully they say, “pack looks good at ten”, but sometimes it’s “pack strung out at ten.” When it’s strung-out, I’ll slow down a tiny bit to help compress the field.

As I reach my mark at Thompson and Palmer, I’ll punch it and zoom into the pits. At NHMS I’ll pull down to the apron and maintain my speed as I glide into the pits, ideally the field will maintain pace.

If the field maintains their pace and no one gets impatient, the starter throws the green, and the field is off in a cacophony of semi-orchestrated mayhem and I sequester myself to a safe place in case I need to dispatch in my new role as – safety car.

Taking Control of the Pack as Safety Car

The role of the safety car is to slow and compress the field in the event of an incident. Once the field is slowed, the various emergency vehicles will dispatch to the scene of the incident to safely remove the disabled car(s) and clean up the course. But mostly I patiently sit, not knowing when and if the poop is going to hit the fan, all the while monitoring both the Flagger and Control nets.

While monitoring the Flagger Net I’ll listen for an excited call. When I hear something like “we gotta’ get this car outta’ here” it’s time to anticipate the call “Pace Car stand-up.” Then it’s “lights on” and reposition to pit-out.

Meanwhile the Flagger Net is busy picking up on the leader’s location so that control can release me in front of the leader.

Sometimes, I’ll get released early and have to wave a few cars by. On rare occasions I get released late and the call comes in “Pace Car, the leader just passed you – go catch ‘em” – that’s a bona fide challenge if the leader doesn’t look in their mirrors, which I suspect the leader isn’t prone to do – until they figure out what all those waving yellow flags mean.

Once the leader is picked up I’ll slow down and compress the field.

When passing by the incident I’ll update control about the progress of the clean-up and try to gauge when they might be clear – that way I may choose to slow down some to avoid an extra safety lap or pick up the pace in anticipation of the restart.

Once the incident is cleared and we’re ready to restart, it’s lights-out at nine, pick up the pace and hightail it into the pits for the green.

It’s important to keep in mind special considerations for different classes. For example, the Formula Vees and Formula 500s are air-cooled, so they need to keep up their speeds to prevent overheating. Some classes like GT1 and Wings & Things can’t go too slow due to their gearing and minimum engine speeds. My favorite group to pace is the “Wings & Things” – my flat-out is their coasting and it’s always a small group; so, giddyap!

Some groups will request a split grid – common with the IT7 and F500 competitors. They’ll leave the grid at the tail end and self-pace; starting themselves honor system style at a predetermined spot. Then there’s the split start, where we’ll use two pace cars – it’s always tricky to position and start the second group without getting overtaken prematurely by the first. It can be nerve wracking for the second group because they know there’s a freight train roaring up from behind.

At the end of the race the pace car repositions back to grid-out. This offers an opportunity to pick up corner reports and to check the course for (as mariners call it) flotsam and jetsam.

It’s always fun (in non-pandemic times) giving members with no track experience a ride in the pace car; you can gauge their anxiety by the severity of the death grip on the car’s grab handle.